The management of rectal cancer has evolved significantly over recent decades. Although total mesorectal excision (TME) continues to be fundamental, the integration of radiation and chemotherapy has been pivotal in advancing organ-preservation approaches (1–4). The "Watch and Wait" (W&W) strategy for rectal cancer, pioneered by Dr. Habr-Gama in the early 2000s, demonstrated that patients achieving a complete clinical response (cCR) after chemoradiotherapy (CRT) could avoid surgery without compromising oncologic outcomes (5). In their 2004 prospective study of 265 patients, 71 (26%) of the patients achieved a cCR and were managed nonoperatively, with a 5-year overall survival of 100% and disease-free survival of 92%, compared to 88% and 83%, respectively, in patients who underwent surgery. Furthermore, subsequent studies, including data from the International Watch & Wait Database (IWWD), encompassing over 1,000 patients across multiple centers, reported overall 5-year survival rates above 85% (6). The OPRA trial (Organ Preservation of Rectal Adenocarcinoma, 2020) further refined this approach, showing that Total Neoadjuvant Therapy (TNT) increased organ preservation rates to 54% when CRT was delivered first, compared to 41% when chemotherapy preceded radiotherapy. Importantly, 3-year disease-free survival was similar between both groups (~78%), endorsing W&W as guideline-supported strategy for patients achieving cCR (7).

However, a key concern with the W&W approach is local regrowth, occurring in 15–30% of patients within three years after a cCR to neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy (6,8,9). While most local regrowths under the W&W approach are salvageable, delayed surgery may impact outcomes. Data from the 2024 ASCO GI Cancers Symposium showed that patients with local regrowth had a 17% rate of distant metastases, compared to 8% in those who underwent immediate TME. This suggests a potential oncologic risk associated with delayed intervention (10). Moreover, the success of the W&W strategy depends on intensive follow-up with imaging and endoscopy, which may be challenging in some settings.

This review provides an overview of the W&W approach in rectal cancer management, covering its rationale, patient selection criteria, assessment of cCR and associated risks. It summarizes current evidence from key clinical trials, highlights practical challenges in clinical implementation, and discusses future directions aimed at improving response assessment and standardizing care.

Clinical Implementation

Patients Selection

The W&W strategy in rectal cancer is most suitable for patients with a cCR after TNT, particularly for locally advanced mid to low rectal tumours (within 6–8 cm of the anal verge)(8). Patients should have received long-course chemoradiotherapy or, preferably, a TNT regimen. The latter has demonstrated superior response rates. In the OPRA trial, patients received TNT as either induction chemotherapy followed by chemoradiotherapy (INCT-CRT) or chemoradiotherapy followed by consolidation chemotherapy (CRT-CNCT), with W&W offered to those achieving cCR. The CRT-CNCT arm showed superior organ preservation (54% vs. 39%, P = .012) and lower local regrowth (29% vs. 44%, P = .02), with similar 5-year disease-free survival (71% vs. 69%). These results support TNT, followed by response-guided W&W as a safe and effective alternative to immediate surgery (7). Another similar study, the RAPIDO trial, showed that Total Neoadjuvant Therapy (TNT) significantly increased the pCR rate to 28.4%, compared to 14.3% with standard therapy (conventional long course chemoradiotherapy followed by TME and optional adjuvant chemotherapy). TNT also reduced the 3-year disease-related treatment failure rate (23.7% vs. 30.4%) and the risk of distant metastases (20.0% vs. 26.8%). However, it should be mentioned here that the RAPIDO trial only evaluated the effect of the TNT. As all patients underwent surgical resection, no statement on W&W could be provided (11).

Beyond tumour response, patient motivation and compliance are crucial. Candidates must be fully informed about the need for intensive surveillance, especially within the first two years, and should be willing and able to participate in this protocol. The decision for a W&W strategy should must be made in a shared decision-making process. Patients with significant comorbidities or poor surgical fitness may particularly benefit from a non-operative approach, although their overall oncologic prognosis must be considered carefully (8,12–14).

Assessment of Clinical Complete Response (cCR)

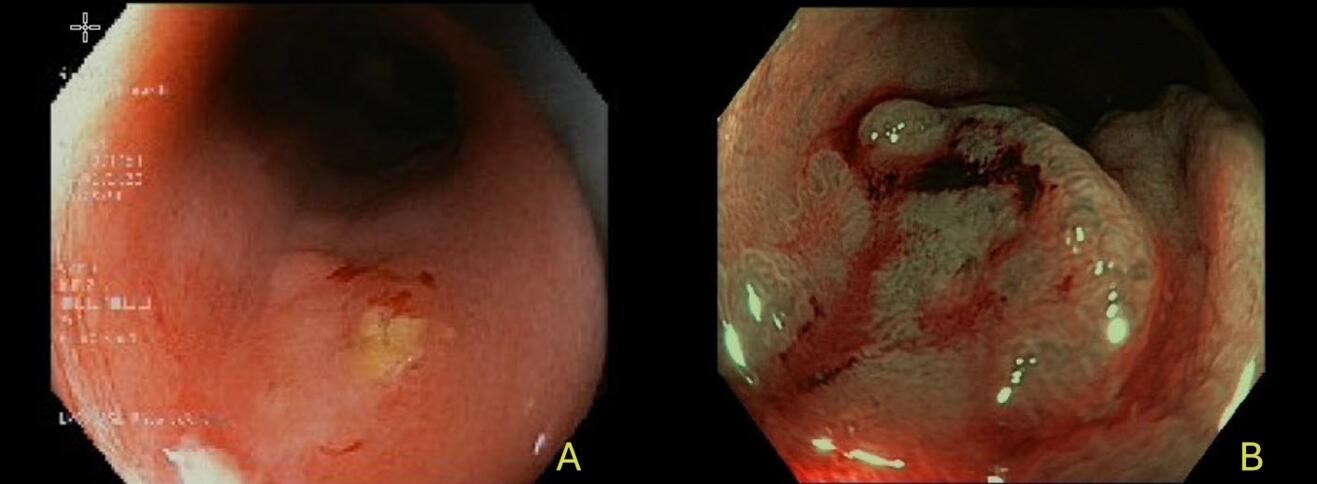

Accurate assessment of cCR is crucial for safely implementing a W&W strategy in rectal cancer (15). A cCR requires the absence of detectable residual tumour after neoadjuvant therapy, evaluated by a combination of clinical, endoscopic, radiologic and laboratory findings. This multimodal evaluation should be performed 8–12 weeks after neoadjuvant therapy, allowing sufficient time for maximal tumour regression. The assessment includes digital rectal examination (DRE), endoscopy, high-resolution MRI with diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI), and carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) levels (16). DRE should reveal no palpable mass - only a soft or fibrotic area. Especially in this case, the experience of the examiner is critical, as minimal differences between scar tissue and residual tumour can be difficult to interpret. On endoscopy, a cCR is characterized by a flat white scar with telangiectasia, without signs of ulceration or nodularity (Figure 1) (17).

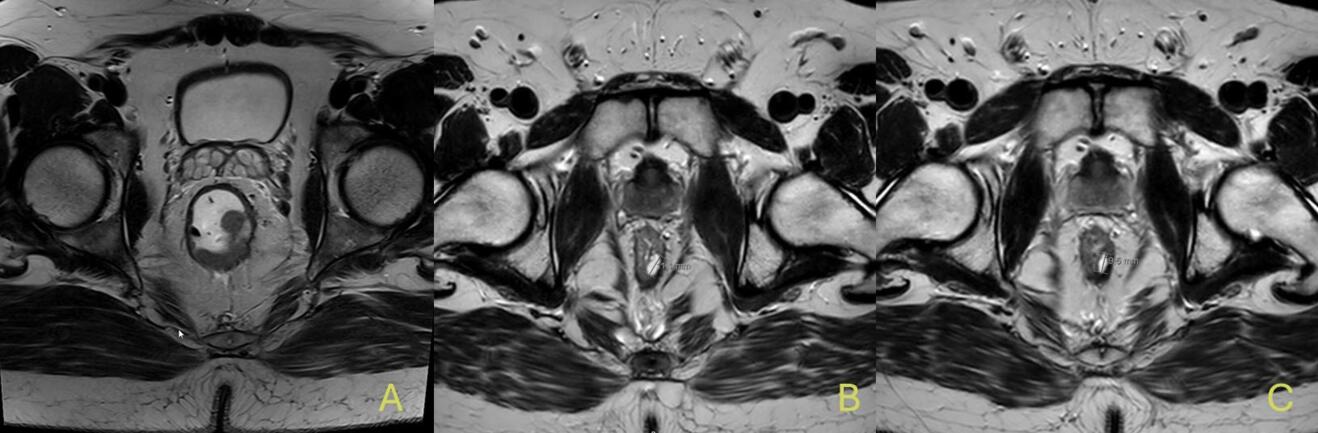

When such typical features of complete response are present, routine biopsies are not recommended, as they may produce false negatives or cause tissue disruption (18). Moreover, high-resolution pelvic MRI is the most informative imaging tool in this setting. Indicators of a complete response include the absence of a visible tumour on T2-weighted images (mrTRG 1–2), no restricted diffusion on DWI, and no suspicious lymph nodes. Small, round, homogeneous nodes are generally considered benign. Accurate interpretation by experienced radiologists is crucial (19). Figure 2 shows MRI scans of a 43-year-old patient from our clinic at the time of initial diagnosis, after completion of total neoadjuvant therapy with cCR, and at the time of recurrence 6 months post-treatment. Interestingly, there is no visible difference between the image at cCR and at recurrence. Studies by Maas and van der Valk have shown that MRI findings, when integrated with clinical and endoscopic assessment, correlate well with pathological response (6,16). Lastly, CEA levels should remain within normal limits and stable over time, as rising values may indicate residual or systemic disease. FDG-PET/CT may be considered in ambiguous cases, but its routine use is limited due to low specificity (18,20).

In conclusion, only when digital rectal examination, endoscopy, MRI, and CEA all consistently suggest complete response can a cCR be confidently declared. Multidisciplinary team review is highly recommended before deciding to proceed with a W&W approach. It is important to note that a cCR does not guarantee pathological complete response (pCR).

Surveillance Protocol

After a cCR has been confirmed, patients undergoing a W&W strategy require an intensive and meticulously structured surveillance program (6). Close monitoring ensures that regrowth can be promptly identified and managed with salvage surgery, which has been shown to maintain excellent oncological outcomes if performed early (21). Surveillance protocols recommend evaluations every two to three months during the first two years, followed by less frequent monitoring thereafter (15). Each follow-up visit typically includes a DRE, endoscopic assessment, pelvic MRI, and measurement of serum CEA levels (16). DRE, as a highly valuable and simple tool, allows to detect early signs of regrowth (6). As well, Endoscopic evaluation allows direct visualization of the mucosal surface to detect minimal changes or nodularity suggestive of recurrence (5). MRI provides detailed imaging of the rectal wall and mesorectal tissues, particularly using T2-weighted and diffusion-weighted imaging sequences, to detect even small-volume recurrences that may not be clinically palpable or endoscopically visible (19). Lastly, CEA levels should be checked regularly, as rising values may precede clinical or radiological evidence of regrowth (22). From our perspective, these follow-up examinations and evaluations should consistently be performed by the same examiner, or at minimum in their presence – ideally by an experienced rectal surgeon. If there are suspicious findings on these modalities prompt biopsy or surgical intervention should be considered (16). In addition, most surveillance programs incorporate periodic systemic imaging, such as chest and abdominal computed tomography (CT) scans, to monitor for distant metastases, although the frequency of systemic imaging varies across institutions.

After the critical two-year window, the surveillance intervals can be extended to every six months until five years post-treatment. Nonetheless, long-term vigilance remains important because late recurrences, although less frequent, have been reported (23,24).

Patient education plays a critical role in the surveillance process. Patients must be fully informed about the importance of attending all scheduled follow-ups, understanding the signs and symptoms that should prompt unscheduled visits, and recognizing that early salvage treatment, if needed, provides excellent outcomes comparable to immediate surgery after neoadjuvant therapy.

Pitfalls

Despite its promise, the W&W approach carries significant pitfalls that must be carefully considered to avoid compromising oncologic outcomes. One major challenge is the potential misinterpretation of cCR. Differentiating true complete tumour regression from residual disease can be difficult, even with the use of high-quality MRI, endoscopy, and clinical examination. Scar tissue and treatment-related changes (inflammation) can mimic tumour regression. Studies such as Maas et al. have highlighted that even experienced clinicians and radiologists face limitations in accurately predicting pCR based solely on clinical criteria, underlining the residual unpredictability involved in W&W strategies (16).

Inadequate surveillance is another pitfall, as delayed detection of local regrowth can worsen outcomes. Strict, protocolized follow-up is essential, since early regrowth detection allows successful salvage surgery in over 90% of cases. According to the International Watch & Wait Database (IWWD) data, delayed detection reduces 5-year distant metastasis-free survival from 94.3% to 73%, highlighting the impact of non-compliance and systemic gaps (6).

Patient compliance and psychological burden also represent significant pitfalls. Long-term commitment to frequent follow-up visits, MRI scans, and endoscopic examinations can be stressful, and some patients may experience anxiety or "scanxiety" during surveillance periods. Moreover, the psychological impact of living with the uncertainty of potential regrowth must not be underestimated. Studies such as those by Hupkens et al. have explored the psychological consequences of W&W and suggested that while many patients prefer organ preservation, the burden of continuous surveillance can affect quality of life (25).

An additional risk lies in institutional and operator-dependent factors. W&W should ideally be performed in specialized centers with extensive experience in rectal cancer management, advanced imaging interpretation, and oncologic endoscopy. Without a multidisciplinary team that includes colorectal surgeons, radiologists, oncologists, and gastroenterologists familiar with W&W protocols, the risk of inappropriate patient selection, misclassification, or suboptimal salvage interventions increases significantly. This has been emphasized in consensus guidelines recommending that W&W be reserved for high-expertise settings (26).

Finally, heterogeneity in definitions and protocols across institutions remains a barrier to the standardized implementation of W&W. Variations in the criteria for declaring cCR, the surveillance schedules, and the thresholds for salvage intervention complicate comparisons between studies and may impact patient outcomes. In summary, while the W&W approach is a promising option for selected rectal cancer patients, its success depens on accurate assessment, rigorous surveillance, comprehensive patient education, and psychological support – all requiring close multidisciplinary coordination.

Risks and Challenges

The W&W is not without significant risks and clinical challenges. One of the primary concerns is the risk of local regrowth, which occurs in approximately 20–30% of patients within the first two years after achieving a clinical complete response (cCR). Most regrowths occur at the original tumour site and are curable with early salvage surgery, which is successful in about 95% of cases according to the IWWD (6).

Another serious concern is the risk of distant metastasis, even after initial cCR. Dossa et al. found no significant difference in cancer-specific mortality between W&W and surgery, with 95% of local regrowths successfully salvaged (26). However, Fernandez et al. showed that 10.7% of W&W patients developed distant metastases, with 60% having prior regrowth. The 3-year distant metastasis-free survival was 75% in patients with regrowth versus 87% in those treated with TME after near-complete response (P < .001). These results highlight the need for careful patient selection and strict surveillance (27).

Beyond oncological risks, there are also functional and psychological challenges associated with W&W. While the strategy aims to preserve anorectal function, some patients may still experience altered bowel habits, urgency, or incontinence due to the effects of radiation therapy. These symptoms may resemble low anterior resection syndrome (LARS), even in the absence of surgery. Moreover, the psychological burden of living with an untreated but closely monitored cancer can be substantial. Many patients report heightened anxiety before follow-up visits, uncertainty about the future, and fear of recurrence. Hupkens et al. reported that despite the desire for organ preservation, some patients ultimately found the psychological strain of continuous monitoring to be more difficult than expected (25).

In addition, the W&W approach presents logistical and system-level challenges. The implementation of a successful W&W program requires a high degree of institutional coordination and multidisciplinary expertise. Many centers may not have the necessary infrastructure to ensure the level of follow-up needed to detect early regrowth or to deliver timely salvage surgery. This has led some expert groups to caution that W&W should only be offered in high-volume centers with proven protocols and extensive experience, as emphasized consensus statements (22).

Finally, variability in practice and evidence gaps remain. Definitions of cCR, surveillance schedules, and salvage criteria differ between centers, complicating outcome comparisons. Ongoing trials like OPRA and international efforts such as the IWWD aim to standardize W&W, but long-term data are still needed for broader acceptance.

Conclusion and Future directions

In conclusion, the W&W strategy has emerged as a compelling, evidence-based alternative to radical surgery for selected patients with rectal cancer who achieve a clinical complete response after neoadjuvant therapy. This approach offers the potential for organ preservation, improve quality of life, and avoidance of the morbidity associated with TME. However, its success depends on rigorous patient selection, high-quality assessment protocols, and strict adherence to surveillance regimens. When implemented in experienced centers with multidisciplinary teams, W&W has been shown to provide oncologic outcomes comparable to those of conventional surgical treatment, particularly when early salvage surgery is available in cases of local regrowth.

Despite these advances, several challenges remain. The risk of regrowth and distant metastasis, such as the psychological burden of prolonged surveillance continue to limit broader implementation. Current evidence supports the safety and efficacy of W&W in high-volume centers with structured follow-up, but caution is advised when considering this strategy outside of such settings.

Looking forward, future directions include the refinement of response assessment tools through the integration of advanced imaging modalities, molecular biomarkers, and artificial intelligence to improve the accuracy of complete response prediction. Ongoing prospective trials and international registries will help clarify optimal surveillance schedules, identify predictors of long-term success, and better define which patients are most likely to benefit from non-operative management. As the evidence base continues to expand, W&W may increasingly emerge as a standard treatment pathway.

- Sauer R, Becker H, Hohenberger W, Rödel C, Wittekind C, Fietkau R, et al. Preoperative versus postoperative chemoradiotherapy for rectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004 Oct 21;351(17):1731–40.

- Heald RJ, Ryall RD. Recurrence and survival after total mesorectal excision for rectal cancer. Lancet. 1986 Jun 28;1(8496):1479–82.

- Srivastava V, Goswami AG, Basu S, Shukla VK. Locally advanced rectal cancer: What we learned in the last two decades and the future perspectives. J Gastrointest Cancer. 2023 Mar;54(1):188–203.

- Habr-Gama A, de Souza PM, Ribeiro U Jr, Nadalin W, Gansl R, Sousa AH Jr, et al. Low rectal cancer: impact of radiation and chemotherapy on surgical treatment. Dis Colon Rectum. 1998 Sep;41(9):1087–96.

- Habr-Gama A, Perez RO, Nadalin W, Sabbaga J, Ribeiro U Jr, Silva e Sousa AH Jr, et al. Operative versus nonoperative treatment for stage 0 distal rectal cancer following chemoradiation therapy: long-term results. Ann Surg. 2004 Oct;240(4):711–7; discussion 717–8.

- van der Valk MJM, Hilling DE, Bastiaannet E, Meershoek-Klein Kranenbarg E, Beets GL, Figueiredo NL, et al. Long-term outcomes of clinical complete responders after neoadjuvant treatment for rectal cancer in the International Watch & Wait Database (IWWD): an international multicentre registry study. Lancet. 2018 Jun 23;391(10139):2537–45.

- Garcia-Aguilar J, Patil S, Gollub MJ, Kim JK, Yuval JB, Thompson HM, et al. Organ preservation in patients with rectal adenocarcinoma treated with total neoadjuvant therapy. J Clin Oncol. 2022 Aug 10;40(23):2546–56.

- Cerdan-Santacruz C, São Julião GP, Vailati BB, Corbi L, Habr-Gama A, Perez RO. Watch and wait approach for rectal cancer. J Clin Med [Internet]. 2023 Apr 14;12(8). Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.3390/jcm12082873

- Park IJ. Watch and wait strategies for rectal cancer: A systematic review. Precis Futur Med. 2022 Jun 30;6(2):91–104.

- Wang QX, Zhang R, Xiao WW, Zhang S, Wei MB, Li YH, et al. The watch-and-wait strategy versus surgical resection for rectal cancer patients with a clinical complete response after neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy. Radiat Oncol. 2021 Jan 19;16(1):16.

- Bahadoer RR, Dijkstra EA, van Etten B, Marijnen CAM, Putter H, Kranenbarg EMK, et al. Short-course radiotherapy followed by chemotherapy before total mesorectal excision (TME) versus preoperative chemoradiotherapy, TME, and optional adjuvant chemotherapy in locally advanced rectal cancer (RAPIDO): a randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2021 Jan;22(1):29–42.

- Horvat N, Carlos Tavares Rocha C, Clemente Oliveira B, Petkovska I, Gollub MJ. MRI of rectal cancer: Tumor staging, imaging techniques, and management. Radiographics. 2019 Mar;39(2):367–87.

- Obias VJ, Reynolds HL Jr. Multidisciplinary teams in the management of rectal cancer. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2007 Aug;20(3):143–7.

- Habr-Gama A, Oliva R, B. P, Scanavini A, Gama-Rodrigues J. Nonoperative management of distal rectal cancer after chemoradiation: Experience with the “watch & wait” protocol. In: Rectal Cancer - A Multidisciplinary Approach to Management. InTech; 2011.

- Smith JJ, Strombom P, Chow OS, Roxburgh CS, Lynn P, Eaton A, et al. Assessment of a watch-and-wait strategy for rectal cancer in patients with a complete response after neoadjuvant therapy. JAMA Oncol. 2019 Apr 1;5(4):e185896.

- Maas M, Beets-Tan RGH, Lambregts DMJ, Lammering G, Nelemans PJ, Engelen SME, et al. Wait-and-see policy for clinical complete responders after chemoradiation for rectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2011 Dec 10;29(35):4633–40.

- Habr-Gama A, Perez R, Proscurshim I, Gama-Rodrigues J. Complete clinical response after neoadjuvant chemoradiation for distal rectal cancer. Surg Oncol Clin N Am. 2010 Oct;19(4):829–45.

- Habr-Gama A, Perez RO, Sabbaga J, Nadalin W, São Julião GP, Gama-Rodrigues J. Increasing the rates of complete response to neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy for distal rectal cancer: results of a prospective study using additional chemotherapy during the resting period. Dis Colon Rectum. 2009 Dec;52(12):1927–34.

- Lambregts DMJ, Vandecaveye V, Barbaro B, Bakers FCH, Lambrecht M, Maas M, et al. Diffusion-weighted MRI for selection of complete responders after chemoradiation for locally advanced rectal cancer: a multicenter study. Ann Surg Oncol. 2011 Aug;18(8):2224–31.

- Probst CP, Becerra AZ, Aquina CT, Tejani MA, Hensley BJ, González MG, et al. Watch and wait?--elevated pretreatment CEA is associated with decreased pathological complete response in rectal cancer. J Gastrointest Surg. 2016 Jan;20(1):43–52; discussion 52.

- Dattani M, Heald RJ, Goussous G, Broadhurst J, São Julião GP, Habr-Gama A, et al. Oncological and survival outcomes in Watch and Wait patients with a clinical complete response after neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy for rectal cancer: A systematic review and pooled analysis. Ann Surg. 2018 Dec;268(6):955–67.

- Smith JD, Ruby JA, Goodman KA, Saltz LB, Guillem JG, Weiser MR, et al. Nonoperative management of rectal cancer with complete clinical response after neoadjuvant therapy. Ann Surg. 2012 Dec;256(6):965–72.

- Davies J, Chew C, Bromham N, Hoskin P. NICE 2020 guideline for the management of colorectal cancer. Lancet Oncol. 2022 Jun;23(6):e247.

- Schmiegel W, Buchberger B, Follmann M, Graeven U, Heinemann V, Langer T, et al. 1344-1498 10.1055/s-0043-121106 schmiegel Wolff W Ruhr-Universität Bochum, knappschaftskrankenhaus, medizinische universitätsklinik und berufsgenossenschaftliches Universitätsklinikum bergmannsheil, gastroenterologie und hepatologie, Bochum. Buchberger Barbara B essener forschungsinstitut für medizinmanagement GmbH, Essen. Follmann Markus M office des leitlinienprogramms Onkologie, Berlin. Graeven Ullrich U kliniken Maria Hilf GmbH, Klinik für hämatologie, Onkologie und gastroenterologie, mönchengladbach. Heinemann Volker V Klinikum großhadern, III. Medizinische Klinik hämatologie und Onkologie, München. Langer Thomas T office des leitlinienprogramms Onkologie, Berlin. Nothacker Monika M AWMF Arbeitsgemeinschaft der wissenschaftlichen medizinischen fachgesellschaften e.V., Berlin. Porschen Rainer R Klinikum Bremen-ost, Klinik für innere medizin, Bremen. Rödel Claus C Universitätsklinikum Johann Wolfgang Goethe Universität, Klinik für strahlentherapie und Onkologie, Frankfurt. Rösch Thomas T Universitätsklinikum hamburg-eppendorf, Klinik und poliklinik für interdisziplinäre endoskopie, hamburg. Schmitt Wolfgang W Klinikum neuperlach, Klinik für gastroenterologie, München. Wesselmann Simone S Deutsche krebsgesellschaft, Berlin. Pox Christian C st. Joseph-stift Bremen, medizinische Klinik, Bremen. Ger journal article S3-leitlinie – kolorektales karzinom. 2017 12 06. Z Gastroenterol. 2017 Dec;55(12):1344–498.

- Hupkens BJP, Martens MH, Stoot JH, Berbee M, Melenhorst J, Beets-Tan RG, et al. Quality of life in rectal cancer patients after chemoradiation: Watch-and-wait policy versus standard resection - A matched-controlled study. Dis Colon Rectum. 2017 Oct;60(10):1032–40.

- Dossa F, Acuna SA, Rickles AS, Berho M, Wexner SD, Quereshy FA, et al. Association between adjuvant chemotherapy and overall survival in patients with rectal cancer and pathological complete response after neoadjuvant chemotherapy and resection. JAMA Oncol. 2018 Jul 1;4(7):930–7.

- Fernandez LM, São Julião GP, Santacruz CC, Renehan AG, Cano-Valderrama O, Beets GL, et al. Risks of organ preservation in rectal cancer: Data from two international registries on rectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2024 Oct 28;JCO2400405.