After several years working in the European healthcare system, I was able to fulfill a long-held childhood dream in the summer of 2025. Inspired by mission doctors and their biographies, I had prepared myself for medical school and successfully completed my studies. I was convinced: one day, I too would make a difference and help people who are less fortunate than myself. However, this idealistic attitude quickly became tempered during my first months as a junior doctor when I realized how far away that goal still was. The initial enthusiasm faded almost completely—until in April 2025, through contacts with Austrian and Swiss doctors experienced abroad, as well as aid organizations like Mercy Ships and Doctors Without Borders, I regained new courage. I particularly sympathized with the organization SIM, which assured me that no completed specialty was required for deployment–whether short or long-term.

I was assigned to a mission hospital in Kenya and began preparing by gathering information about the region and studying the hospital’s specifics. However, in mid-May, I received news that no help was needed in the surgical department in Kenya, my desired field. Instead, I was asked if I would be willing to assist in the northwestern province of Kasempa in Zambia. Having little insight into the different cultures and countries, and simply glad to be needed and to realize my dream, I accepted.

Shortly thereafter, I received essential information: necessary vaccinations such as yellow fever, daily malaria prophylaxis, the two main seasons—rainy and dry—as well as advice about the short days and the strong recommendation to bring a reliable flashlight to avoid stepping on snakes at night.

Prior to my departure, I learned about the enormous linguistic diversity in Zambia: besides the influence of the former British colony, evident in left-hand traffic and English as the official language, there are 72 indigenous languages and 73 recognized ethnic groups, so-called “tribes.” Seven regional languages are officially used, including in schools and government offices.

After flying from Vienna via Addis Ababa, I finally landed in Lusaka, where I shortly afterward boarded a small plane to Mukinge. Jason, the pilot—a young, talkative American—shared stories about his many years of experience in the region and its diverse wildlife. From the air, numerous rivers, swamps, and small lakes were clearly visible. “Zambia holds 30% of Africa’s water resources. This river is teeming with crocodiles and hippos. This is a nature reserve about the size of Switzerland. Over there are the fields where the maize is currently being harvested,” he explained.

During the hour-and-a-half flight, I learned a great deal about the surroundings. The flight spared me a twelve-hour drive over unpaved, dusty roads, partly covered near towns with remnants of processed sugar beet—an agricultural measure to improve soil and reduce dust.

Upon landing without incident, I was picked up by Dr. Samuel, my assigned supervisor, and his wife Alexa, who took me to my accommodation. After a brief orientation on dealing with power outages and the advice to drink only boiled, disinfected, or filtered tap water, I felt ready to accompany Dr. Samuel, a general surgeon, to the hospital right after arrival.

At the entrance of Mukinge Hospital, one immediately notices a cross embedded in the floor tiles—a symbol of the hospital’s Christian origins and values lived daily here. Founded in the 1950s as a mission project of the Evangelical Church in Zambia, the hospital was deliberately established in the heart of the medically underserved Kaonde population. An important goal was to combine medical care with Christian service—healing both body and spirit.

This ethos still shapes the respectful, attentive, and compassionate interaction among staff and with patients.

Across the street from the hospital entrance, a tent is set up where several people sit waiting on benches. “This is the triage and outpatient emergency area—currently, the hospital rooms are under renovation,” I was told.

A brief tour of the health facility left a positive impression. The hospital has 200 beds and offers a wide range of services, including emergency care, obstetrics, pediatrics, general medicine, ophthalmology, dentistry, and surgery. Alongside prevention programs and health education for the Kasempa region’s population, the hospital is an important center for training medical staff. Speaking briefly with a nurse, I learned that the government-accredited nursing school in the northern part of the country is highly popular, attracting students from the Copperbelt region to train here.

The hospital also has a laboratory that primarily measures hemoglobin and creatinine levels and conducts tests for malaria, HIV, and tuberculosis available to every patient. Although other parameters and even microbiological cultures can be performed, these are rarely requested due to cost. Doctors of various specialties communicate via a WhatsApp group called “Lab” about the availability of erythrocyte concentrates—scarce resources—and test updates. It is estimated that around 20% of the local population is HIV positive, confirmed through patient testing. Besides HIV-associated illnesses, tuberculosis, asthma, and malaria are common diseases. Many young children only come for treatment on the third or fourth day after symptom onset, often suffering severe consequences of malaria infection. To prevent tuberculosis spread, signs listing symptoms and behavioral recommendations are placed at the village entrance.

We then visited surgical patients, mostly hospitalized for trauma reasons such as fractures, finger amputations, skull contusions, and large crush wounds. “Did you see those four riding a Honda on the road without helmets? Most patients here are victims of traffic and mining accidents.” I learned that gold was discovered in the region a few years ago, attracting many private miners due to a lack of state regulation. Some are trained teachers, nurses, workers, and even doctors who considered mining. This often leads to severe and sometimes fatal injuries. While most fractures are treated conservatively with prolonged traction techniques, a team of orthopedic surgeons visits monthly to determine surgical indications and perform operations. Skin grafts after burns or traumatic injuries are also common.

Due to limited resources and a narrow selection of antibiotics (amoxicillin, doxycycline, ciprofloxacin, metronidazole, ceftriaxone, and cefpodoxime), as well as a lack of equipment, treating infected wounds is prolonged, involving regular wound irrigation, debridements, and application of honey dressings. Natural honey from local Mukinge beekeepers is purchased by the hospital for about 20 USD per 25-liter bucket due to its antibacterial properties. Occasionally, pressed papaya—called “PewPew”—is applied to wounds, especially when honey supplies run low. One patient has been undergoing this treatment for three months. During the last rainy season, he was fishing in the river near the village when a hippopotamus attacked, biting him multiple times in the lower back and right thigh. Only his quick thinking and courage saved his life: with a pocket knife, he injured the hippo’s eye, causing the animal to release him.

The number of abdominal surgery patients was manageable. There was one abdominal gunshot wound and a typhoid infection treated with bowel resection and stoma formation. Otherwise, elective procedures like open hernia and hydrocele repairs were often performed on young and adult patients.

Patients with diarrhea were treated by the physicians, and during my stay, an open appendectomy was performed on a young woman with appendicitis. Although laparoscopic procedures are planned for the future, the necessary equipment is currently lacking.

I quickly realized that most surgical patients had almost no relevant comorbidities such as heart disease or diabetes. I did not see any anticoagulants during my entire stay, and even immobilized patients treated with traction received no thrombosis prophylaxis.

For diagnostics, an X-ray machine and an ultrasound device are available. Two leading surgeons even carry a mobile Butterfly ultrasound probe connected to an iPhone. X-rays are also accessible via the hospital network on iPhones. Thanks to Starlink, the entire facility has good internet access over Wi-Fi.

The following days established a gradual routine. At 6:30 a.m., ward rounds on the surgical wards began with Dr. Osteen, a retired general and vascular surgeon from Houston, Texas, who has contributed his expertise annually for one to four months over nearly ten years. His humble approach to patients immediately struck me, as did the respectful, trust-building physical contact during rounds. “It makes no sense to swallow medicine if the doctor doesn’t touch me during the visit and thus I cannot get well.” Such statements surprised me and helped me understand how important physical contact is for many patients—much more than a friendly gesture, but vital for compliance. Time and again, I saw patients whose treatments were completed bidding farewell to Dr. Osteen: “Thank you, Father of the Nation!” to which he replied with a smile, “You’re welcome, son.”

During my stay, I also worked closely with Dr. Friend from New Zealand, who has lived and worked in Mukinge for over 20 years—not by chance, but out of deep conviction. His faith led him to this place where the need was greatest. His experience and international network are essential pillars of the hospital’s surgical care. I was especially impressed by his dedication: he cares not only for hospital patients but also regularly visits prison inmates and people in a nearby leprosy colony. He is a professional and personal anchor for many.

After morning rounds, the medical staff meet in the hospital chapel. After a brief devotion led by the hospital chaplain and a joint prayer, the main patients and problems from the night shift are discussed. There are also hospital updates and introductions of new colleagues. Afterwards, everyone goes to their respective departments.

The morning briefing includes planned surgeries on the board. Three large operating theaters are available for major procedures, plus two smaller rooms for wound care and minor surgeries. Depending on need, I am also assigned to work independently in the smaller theaters or perform procedures like cesarean sections, hydrocele, and open hernia surgeries under supervision.

I am guided with great patience by Dr. Samuel, an Egyptian expatriate surgeon from the PAACS program. His vision is to expand surgery locally so that the hospital one day becomes part of the African PAACS surgical training program to strengthen and improve networking and care on the continent. “Do you see those scars in the groin?” “Yes,” I replied. Two small scars about five millimeters in size were visible in the hernia region. “Is the patient operated on before?” I asked. Dr. Samuel laughed, asked which surgical technique was used, and finally explained: “These scars are called tattoos. They are cut into the skin by the witch doctor to drive the illness away from the body.” Since that insight, I noticed such tattoos repeatedly—over old fractures, hernia areas, or above the lower abdomen in some women.

At noon, it is traditional to eat with the hands here. One of the American doctors takes care of feeding the surgical team through the hospital restaurant. Anyone who wishes can get a serving of nshima with side dishes for lunch every day. Nshima is the traditional staple food in Mukinge, made from maize flour. It is not only the main basis of meals but also an expression of community and culture. We shared personal experiences and planned how to spend the afternoon together after work. Before my journey, I received intercultural training, where eating with the hands was also explained.

The hospital also has a room with weights that belongs to the physiotherapy department. Anyone who wants can train a little there after work. Otherwise, there is a steep hill that is often used for hiking. The 6-kilometer hike after work became a routine for me whenever time allowed. At the foot of the hill, the harvest of local maize takes place, which is then collected in sacks weighing about 60 kilograms and loaded onto trucks. I was even once invited by the workers to help out, which was a fun experience.

On my way home, I pass by the public basketball court. Mostly children and teenagers play basketball there. They told me that there is also a soccer field near the Nursing School. Besides that, there are not many recreational opportunities in Mukinge. They also told me that schooling here goes up to the 7th grade. When I asked what they wanted to become, one replied, “Doctor, lawyer, or engineer.” – “And where can you continue your education?” – “In Lusaka.”

After 6 p.m., the streets are almost deserted. Since the sun sets early and it gets dark quickly, most people retreat to their homes to avoid mosquito bites. The rapidly increasing darkness makes me very tired. I look at the clock – it’s only 8 p.m., but it feels like midnight to me.

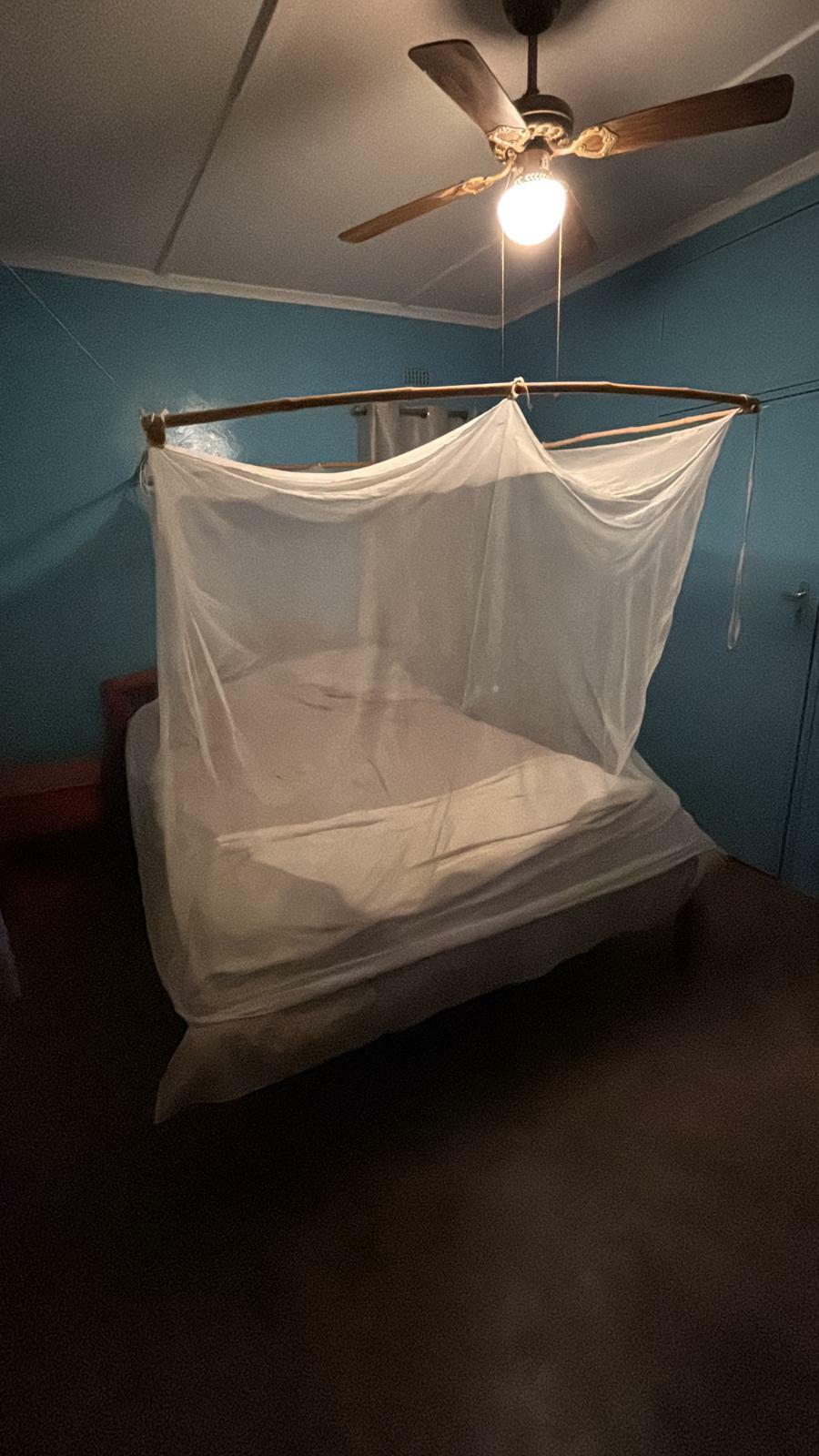

After the evening shower, during which I always leave a lot of dust in the bathtub, I lie down in my bed protected by a mosquito net. To keep the mosquitoes away, I tuck the hanging part of the net under my mattress so I can fall asleep peacefully.

My stay at the Mukinge mission hospital was an incredibly enriching time for me. In a short period, I was able not only to experience firsthand the medical challenges in a resource-limited region but also to feel the warmth and solidarity of the local people. These encounters and experiences shaped my perspective on life, medicine, and my faith.

Although I cannot currently imagine a longterm assignment, I now know how valuable such short-term missions are – they offer not only professional insights but also personal moments of growth that resonate long afterward. I can well imagine returning for a few months in the future to continue learning, helping, and being part of this special community.

For me, it has become clear: Anyone open to new experiences and wanting to make a contribution should not shy away from spending such a time abroad. It opens new perspectives – both professionally and personally – and leaves lasting impressions. I am grateful for the opportunity to have gotten to know Mukinge and look forward to undertaking similar missions in the future.